“If an artist is going to come to a print shop, that’s like getting naked. They can’t hold anything back. I’ve found that most of the mediocre prints that I have done are because I can’t get an artist to open up.”—Erika Greenberg-Schneider

Erika Greenberg-Schneider: Founder + Master Printer, Bleu Acier / Tampa FL

bleuacier.com

“if an artist is going to come to a print shop, that’s like getting naked. they can’t hold anything back. i’ve found that most of the mediocre prints that i have done are because i can’t get an artist to open up.”—erika greenberg-schneider

Are your relationships with the artists collaborative?

It changes from artist to artist. Certain artists have an established history; they have a developed body of work and they know what they are doing in printmaking. They don’t necessarily want to develop new research when they have a very specific project in mind. In this case, I become a facilitator. And I’m fine with that. Artists expect a certain professional demeanor from a printer. No matter how perfectionist you both are, or how much both of you think you know, there’s always that moment when you’re confronted with an issue. Then the ideal has to shift slightly. But for me, this is an example of a silent collaboration.

Bleu Acier Studio

courtesy of bleu acier

Then there are the virgin printmakers, and I’ve specialized in working with them since I started Bleu Acier in 1998. These artists have usually never made a print, and usually have never been interested in printmaking until their work begins to sell. A gallerist or publisher will approach them in order to discuss the possibility of publishing prints, and hopefully the printer has enough culture and referential knowledge to advise.

I never tell an artist, “We should make a 12-colored X.” They need space and I want to see what their reaction is. Usually what happens, the collaboration ends up working or not working within that first hour. The artist either likes or dislikes the perception that the printer has of their work. Starting with their work as a foundation, you keep questioning how it can translate into this other medium. I become the facilitator and accompanist. I want it to be their image and not mine. There are moments in this relationship where the artist has to allow me ownership before I can give the image back to them.

How do you decide what artists you want to work with?

Shops tend to be either fine art print publishers or contract presses. I do both because I need to earn my living in order to print what I want, but I do both lovingly. I also teach because it provides me with the viewpoint of a young set of thinking processes, which helps me grow. A lot of printers like to be purists about the work that they choose to do, but I’m happy with both kinds.

I am selective with whom I work on contract projects. I only work with people who understand what my specialty is and the skill sets that I can offer. I learned my trade in France and lived there for 25 years. I love the way French artists think about space, and the French painters and sculptors that I’ve worked with consider printmaking a high art. They have real respect for the trade and the work that’s made. They are real collaborators.

I live and work at Bleu Acier, therefore an artist who comes to work with me also lives and works in the same space. Artists become intertwined with my family. Some choose to stay elsewhere and that’s fine with me, but most of the people that I bring in really want to be a part of my shop and home. It is important to me that collaborations go beyond the shop. As a master printer, you are intimately involved with somebody else’s work, and you can’t be intimately involved unless you know a lot about them. It sounds banal, but to be able to take a walk together on the beach, really impacts their ability to open up to you in service of the artwork. In the long run, knowing somebody you work with is fundamental for the outcome of the image.

After this initial in-person experience, do artists come back to your shop, or do you collaborate remotely?

It depends upon the image. There are several exquisite photo-based print techniques, such as photogravure, that allow the artist to send me digital photographic files or hand-drawn Mylars, and the work can be completed using email and mail. We sometimes start the work by mail so that we can be really efficient when the artist is in my shop.

How important is the initial face-to-face meeting?

I think that physically meeting has a lot to do with where the collaboration heads. In the collaboration, I react to what the other person says. Really excellent master printers understand this about collaboration. You can see it in the work—that moment when the artist comes alive and gives up to the printer. The image then belongs to the printer but that can only happen with a certain amount of trust and confidence. Then at one point, which is always the hardest point for me, the printer has to admit that they’re done and give the image back to the artist. A miraculous moment happens when the artist gets it back and calls it theirs. When an artist tells me that the experience they had working with me will help them grow in their studio, I know that I have succeeded. I know when I do great work versus when I get bored with something.

Is boredom a reflection of not understanding the artist?

That is the only reason. Or when artists are selfish with their work. If an artist is going to come to a print shop, that’s like getting naked. They can’t hold anything back. I’ve found that most of the mediocre prints that I have done are because I can’t get an artist to open up. When I don’t have anything to work with, the prints end up reflecting this.

What is your collaborative process in the shop?

It depends on the designer. Usually we start by discussing size of the image, process, number of colors, size of the edition, and paper choice.

I worked with Abbott Miller and Ellen Lupton when I was the Master Printer of Intaglio at Graphicstudio, USF Tampa. I’m not sure that any of us really understood what our working relationship to each other was at first. Abbott and Ellen were so used to working together and all of a sudden they had several printers at their disposal. Initially, there seemed to be difficulty in comprehending the goals of the image. Their typography research was extensive and influencing the goals for the edition. The first results were good, but not spectacular. I was up to my elbows in ink because I loved the idea of type as image but had never worked on a project like it. We continued the collaboration remotely. Part of the trouble was in the differing ways that we saw space. Type on screen is not the same as type within the materiality of printmaking. Scale in material processes is also far removed form the idea of digital scale, and we were working with photogravure, not letterpress. What made that collaboration great was that everybody was able to roll up their sleeves and not have issues with artist/designer labels.

Hervé DiRosa is a French painter and for the past two decades has been involved in what he calls his “world tour.” Married to a diplomat, he moves to a new location every 4–5 years. He develops projects using the know-how of that particular country/state/region/city and then brings it all back to Europe for exhibitions. While in Miami from 2004–2008, we made prints of this journey. He loved the culture in Miami and that translated through the signs painted on buildings to the sequin artisans of Haiti. Always having to go back and forth to his base in Paris, we developed a system. His love is stone lithography. I would grain the stones and take them to Miami, so when he would be in town, he would execute the images, and then I would go back to pick them up. Here at Bleu Acier, I would proof and send him images via video or email, and if they were good, I would print the editions. Then I brought them back to Miami where I assisted him in the hand painting of the editions. His non-flexible schedule meant having to work around it.

Do you have many graphic designers come to you?

The first project with Paula Scher was reproducing her political journal as prints. Abbott Miller had introduced us and Paula had made many successful serigraphs over her career. Straight reproductions are tricky, even in photo-based printmaking, so compromise needs to be reached when shifting from drawing to printmaking. At the beginning, I was not sure what she wanted, so I just started making things. I wanted to meet her and discuss the images and understand what she wanted. I met a woman with a fabulous sense of humor, who is really good at what she does, and is a very political intellectual. Because my collaboration with Paula was going to be all about the endgame, I didn’t have much leeway on my first project with her. We had to think of a way to make prints that were as interesting and original as her type drawings. We ended up enlarging the original drawings through photogravure, and then Paula hand painted the color. That brought it into a painterly space and the results were stunning.

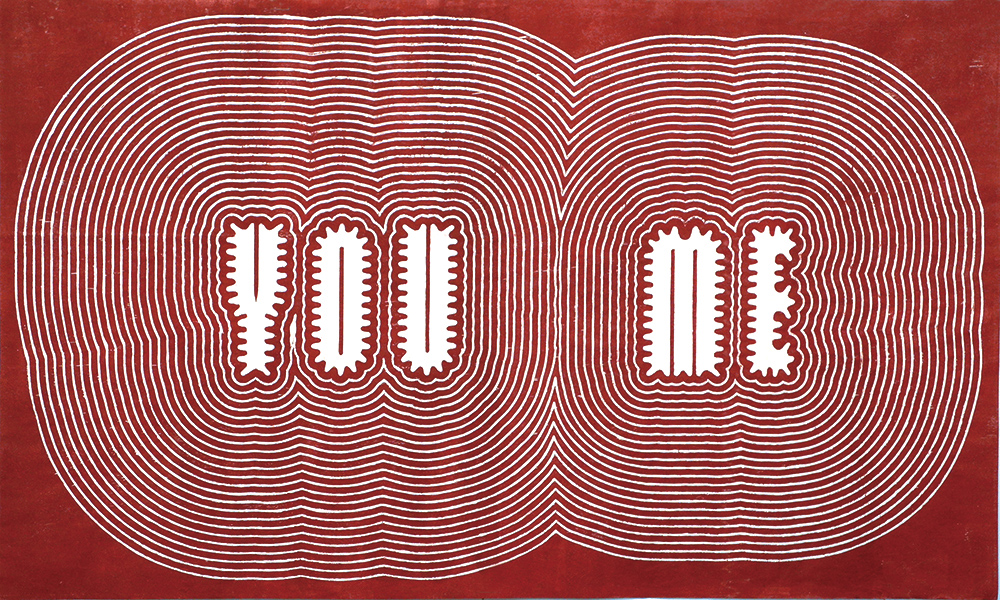

You Me

paula scher + bleu acier

courtesy of artists

We were looking through her oeuvre, and I found an image that I loved and asked if we could publish it as a print. She answered, “Oh sure, do whatever you want with it.” This was a new and different kind of collaborative process for me. I had this great idea to make a very small gravure of it. I was so proud. I brought it to her beaming, and she stated that she always imagined this image big. I realized that this work depended on scale and we needed to reflect that. The image sat in my shop for six years. I kept looking at it; I kept wanting it; I kept wanting to make it. I decided I was going to do an experiment. Paula draws and paints these fabulous maps. I started thinking about the possibility of a big, low-tech, woodcut to contrast the type image made so perfectly in Illustrator. I proposed to break it, to force the medium to make as powerful of a statement as the image. I had a plotter print it big in vinyl, then we stuck the vinyl on the wood, and then we cut and we cut and we cut. It was huge. It was much more difficult than I thought it was going to be because the lines were complex. Silkscreen was the obvious answer, so I wanted to avoid that. I wanted something challenging. When we pulled the first proof, I was speechless—it was gorgeous.

Do you ever feel like you are not credited for your role in a collaboration?

I think a lot of students assume that there is something romantic and sexy about printing for other artists. Schools have programs for bringing in visiting artists and running prints. But that’s a different vibe than doing it every day and having different people at your shop each week. It is important to understand that printers are somewhat of an interpreter, or ghostwriter. It’s more of a silent partnership between the artist and printmaker. When a print is shown in a gallery or museum, the shop and printer’s name are written below the artist. I get recognized for what I do, but I don’t need more than that. The relationship that I have with that person is a gift enough. I love making images in print, but I just don’t want to do it for myself. So collaboration is a very good solution.

Rock Wood Water Earth

dominique labauvie + erika greenberg-schnieder

courtesy of bleu acier

I know many printers who have personal bodies of work, but that are not famous or known for it. Their primary activity is working with other artists. I make work, but showing it is not my priority. I’ve been making books since I was 12, but I don’t feel the urge to show them. It’s like 90% of graphic design work: it doesn’t have a name on it.