“The hope is that all of us are following projects all the way through, instead of each of us adding our own little wisdom, and sending it down the conveyor belt to never see it again. That is definitely a benefit of having a really small team.”—Jordan Bass

Jordan Bass: Editor, McSweeney’s / San Francisco CA

mcsweeneys.net

“the hope is that all of us are following projects all the way through, instead of each of us adding our own little wisdom, and sending it down the conveyor belt to never see it again. that is definitely a benefit of having a really small team.”—jordan bass

Can you talk about the McSweeney’s process? How does a project come in, and what is its evolution?

I mainly work on our quarterly. There is a definite process for it each time. One idea or approach will end up becoming the center of gravity for whatever we are doing. There are things that we adhere to. Sometimes that starts out of a collaboration with someone, with a writer or another editor who has an idea that might be a good fit for us. But the consistent motivation is trying to do something new with the magazine every time. We continually try to push it in new directions and press the edges of what a book can be, or what an anthology can be. In the last couple of years, we have been thinking more specifically about pushing it beyond ten or twelve great short stories. We are up to that kind of collaborative challenge. And we are in a lucky position where people will bring their good ideas to us.

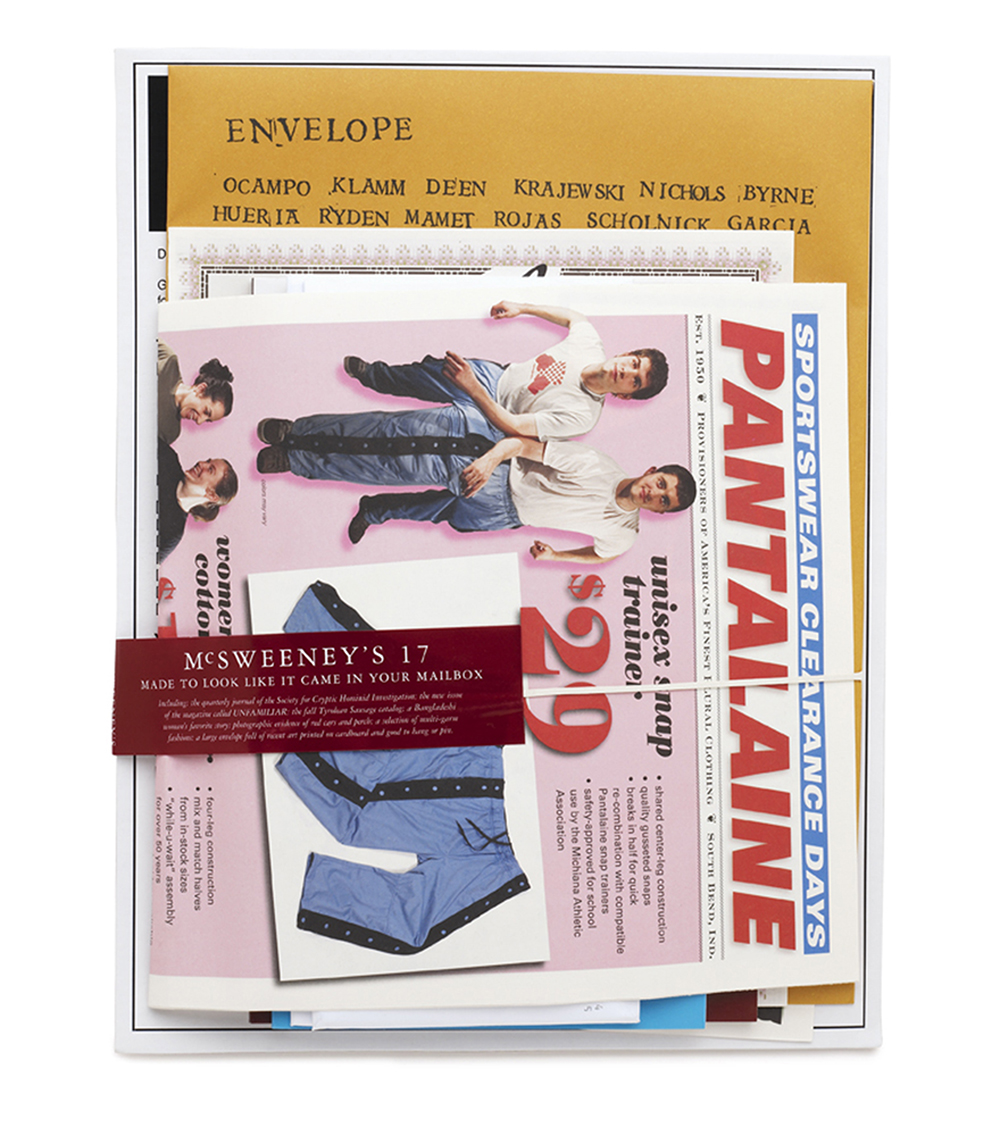

McSweeney’s 17

courtesy of mcsweeney’s

Is that something that you actively try to develop with people? Or is that more about people knowing you exist?

I think a lot of it has to do with the latter—having a little bit of history of being a magazine that is able to do that. Even back in the earlier issues, that is how Dave Eggers worked a lot of the time. When he brought in Michael Chabon or Chris Ware to edit those earlier anthologies, a lot of that did just come out of conversations between those guys, and hearing the kind of ideas that they had. Dave encouraged them to pick up the ball and run with it. McSweeney’s has a willingness to hand over control for an issue. We are conscious of having that freedom. The magazine doesn’t have a consistent page count, size, recurring features, or columnists that you have to give space to every time. It is a blank canvas.

Sometimes we will pursue people. A project will start out with an internal idea, and then we will go after people to fill in different parts of it. But most of the time, the content comes out of people approaching us.

What makes a certain author or editor or topic a good fit for McSweeney’s?

The core of the magazine is still short stories, or storytelling, as well as new, ambitious, and interesting writing. Having an author that has a new angle on that is important. Adam Thirlwell, for an example, is a young British novelist who came to us with this idea of thinking about how translators work, how they thought of themselves in relation to writers, and he ended up curating this project for us that turned into a full issue of the quarterly. There were 60 different fiction writers serially translating a set of pieces so that they would go into English, then back out of English, then back into English, then back out of English, over and over again. Adam had an early version of that idea when he proposed it to us. Then it became a matter of thinking about whether it was rich enough to become an issue of the quarterly—whether it gave us a platform for a book that was worth reading. We were really happy with how that quarterly turned out because it was something that had a very coherent idea behind it, a lot of interesting questions to explore, and a lot of different directions for people to go in. That is definitely part of our process: looking for an idea that will be able to fill that canvas.

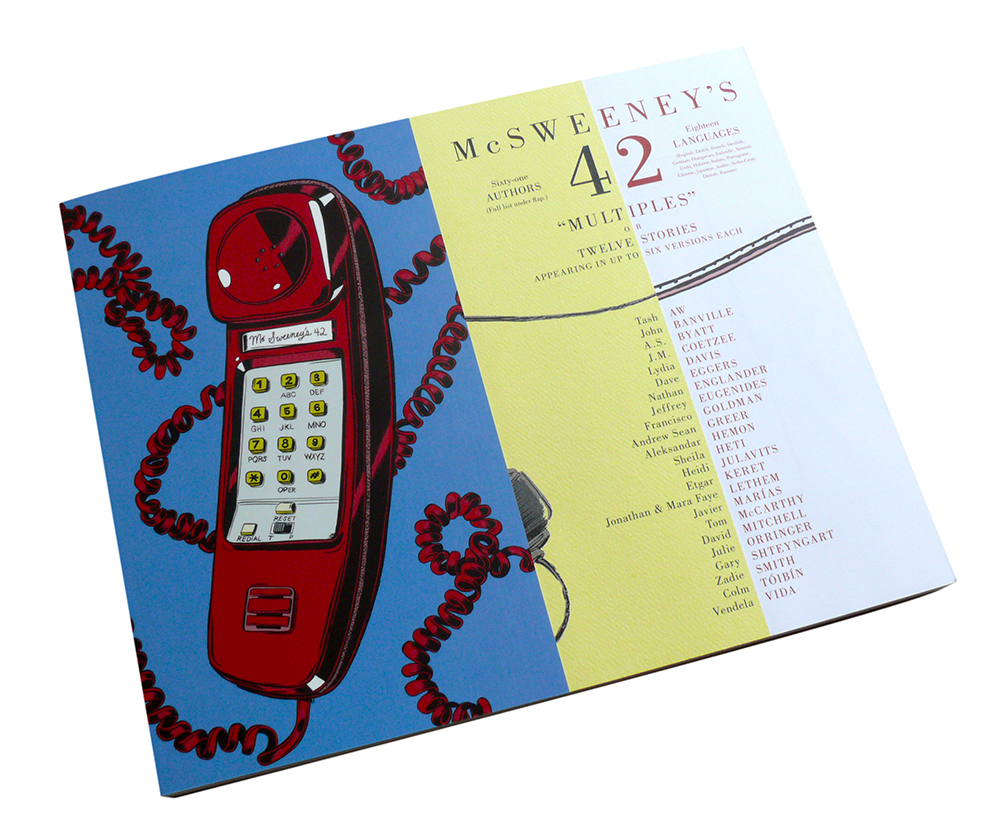

McSweeney’s 42

courtesy of mcsweeney’s

You mention people like Chris Ware and Michael Chabon, who have repeatedly been involved. How do you develop that community?

I think it happens in different ways. I keep coming back to this idea that we are in a pretty lucky position. I don’t know that there is always a particularly firm, pre-existing community before these collaborative projects come about. We are based out of San Francisco. We are kind of off the grid of contemporary publishing and writing, to some degree. Our contributors are all over the world. There isn’t one central cluster of people that we work with.

A lot of it is a spontaneously incarnated community around a given project. When we reach out to someone, people are very generous about answering our emails and taking our calls. We try to be receptive in the same way when someone comes to us. I think that is a little bit different from when the magazine started. Dave was in New York and very consciously pulling together a set of writers who he felt were underrepresented. That’s when he started to work with John Hodgman, Sarah Vowell, and Arthur Bradford. Dave threw events and tried to bring people together in person. It has become a much more distributed endeavor since then and we maintain that by not letting it freeze into one shape.

With all of the online forms of distribution, tools, and communication, does that help you build the community, or does that make it harder?

In a lot of ways, we couldn’t exist without an online presence, certainly in terms of the readership and a community around the book. That whole digital world has been totally essential to us. It makes it so much easier to put ourselves in front of people when it lets us send work all over the world. On the side of creating these things, I don’t know how to evaluate it qualitatively; it’s just different. It opens different doors. It pushes us in a different direction. If we were forced to work with people in a 20-block radius, it would be a very different magazine than it is now. Now, we can get a person to edit a section in Norway or Kenya or Australia. I hope it would still be a good and interesting magazine.

Does having so much of the production happening in-house, facilitate collaboration?

Yeah. It’s hard for me to answer, because it’s the only way that I have ever worked on a magazine. The different layers are pretty permeable. I can talk to the art director and printers directly. The hope is that all of us are following projects all the way through, instead of each of us adding our own little wisdom, and sending it down the conveyor belt to never see it again. That is definitely a benefit of having a really small team. Everyone is invested and aware of every aspect of a project. People are conscious of how a shift on one end will affect something on the other end.

In that translation issue that I was talking about, the one that we did with Adam, going into it editorially, we thought about how somebody could meaningfully experience a book that had 19 different languages in there. In a way, we were creating this thing that was not going to be completely accessible to anyone except highly polyglot people. It became a project where the editing and the design felt like they were informing each other about how to make it as transparent as possible and as readable as possible. We thought about how somebody could move through the book when they were constantly being kicked out of it, like when the text switched from Hebrew to Chinese. We came up with a purposeful design that let us run different stories alongside of each other, so we maintained this consistent thread of English text all the way through the book. I wanted there to be something on every page for every reader. That was definitely a process of going back and forth with our designer, and with Adam, and with our printer, trying to figure out how to accommodate that. It was a very fluid process because I was sitting two feet away from the designer, and we could pass the InDesign file back and forth, which meant that I could be moving things around right after he did. I think that openness allows for a pretty quick evolution of the project.

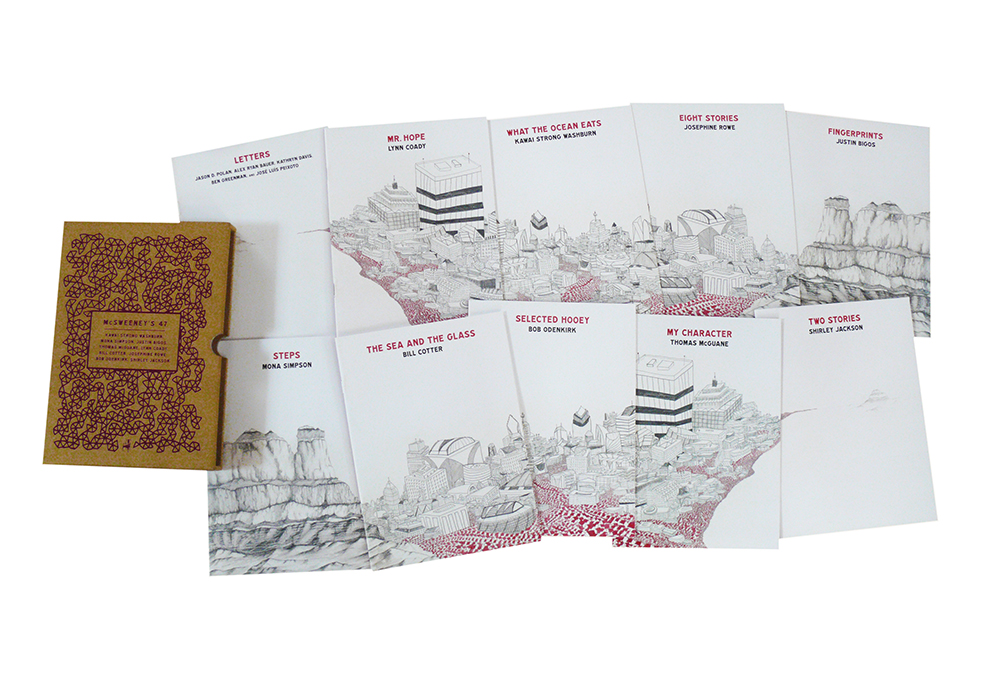

McSweeney’s 47

courtesy of mcsweeney’s

Do you have a dream project? Is there a particular thing that you want to try?

We are always thinking of new possibilities. We’ve run into different barriers. For a while now, we’ve been talking about a pretty ambitious project with a group of photographers here, and working with a different Bay Area community. I’m also trying to give the same sense of range in bringing together a group of writers. It has progressed into a pretty formidable printing challenge, so that is something that we are still working on. I would love to do another project with Adam. That issue was definitely a lot of fun. Dave always wanted to print an issue on glass. He still has a lot of unfulfilled dreams.

Does the relationship feel different when working with an author outside of McSweeney’s?

Yeah, I think it does. We definitely think about that as a collaboration. A lot of our process is about aligning McSweeney’s with the writer, trying to understand their intentions, and thinking about how we can help realize those. That is always a huge part of the magazine—trusting that we can offer something meaningful for a writer. Everything that we publish has been pretty well worked over by the time that it has hit the world. Writers are generally really responsive to that. It can be a compelling and useful process to have someone in our position reading a story very closely and trying to understand how it works and trying to hone it as much as we can. Working on individual pieces, or individual products with writers, is a huge amount of the collaboration that we do from day-to-day.

How have you been able to continue to have a footprint, and keep putting things out, despite the state of the print industry?

I wish I knew. We would do twice as much work if we knew exactly. The truth is that we try to over-deliver as much as we can. We run the zine as a lean organization and pack as much into each issue as we can manage. The hope is that people remember that, and respond to that, and come back to us wanting to know what the next thing is that we are going to do. That landscape that you are talking about, with so many alternatives, puts the onus on us to come up with something that is as interesting as we can make it. I think we are very conscious of that. We have never been the only game in town and it’s also how we started out: McSweeney’s started as a very small operation trying to shoehorn its way into people’s attention. That has always been our instinct. We have never had it easy.