“There is never a collaborative experience that doesn’t suck at some point along the way.”—Mike Weikert

Mike Weikert, Director + Ryan Clifford, Assoc. Director: Center for Social Design, MICA / Baltimore MD

micasocialdesign.com

“there is never a collaborative experience that doesn’t suck at some point along the way.”—mike weikert

What collaborative programs do you run at MICA?

Mike: The Center for Design Practice is a way to take students from different disciplines within MICA, and have them partner with an outside entity around a social problem. I wanted students working on real-world challenges. We were able to funnel these opportunities to something less constrictive than a class. There were some cross-country collaborations, where an idea would be implemented in Detroit or Minneapolis. Since 2008, we have worked with 20+ partners, and hundreds of thousands of dollars in funding. Ryan now manages all of the CDP projects.

MICA Center for Social Design (CSD) North Avenue Studio Space

courtesy of mike weikert + ryan clifford

The CDP quickly became an attractive experience for students. We got information back from students saying that the experience provided skills, knowledge, and poignant viewpoints that were helpful when interviewing for internships and jobs. We expose students to the concept of collaboration. We expose them to the concept of design working toward social change. We expose them to outside stakeholders. Projects end up spilling over and carrying on for multiple semesters. We are trying out ways to embed social design practices into the undergraduate design curriculums because we want students to develop a social literacy before they come into the CDP.

As a result of that, we developed the MA in Social Design Program (MASD) in 2010. Now we have a graduate program that is a one-year, intensive, practice-based experience. Students come in from different disciplines in design or fine art, and we layer social skills on top of their core design skills, including ethics, teamwork, collaboration, social literacy, design research, design thinking, entrepreneurship, and sustainability. All of these skills are necessary in social design practice, but the core skill is collaboration.

MICA CSD North Avenue Studio Space

courtesy of mike weikert + ryan clifford

The third initiative that we’ve developed is a postgraduate fellowship program, where two of the graduates from the MA in Social Design Program are funded to stay a second year and continue their thesis work.

We recently moved into our new studio center. The idea was to consolidate all of these entities into one lively entity called the Center for Social Design. We have undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate students in the same workspace. It’s our lab, or collaborative makerspace. Universities are seeing the benefit of sharing knowledge across disciplines. Universities are buying into the idea of building an incubator. The idea was inspired by artists and designers, but now it’s happening in disciplines outside of art and design.

MICA CSD North Avenue Studio Space

courtesy of mike weikert + ryan clifford

Is there program crossover?

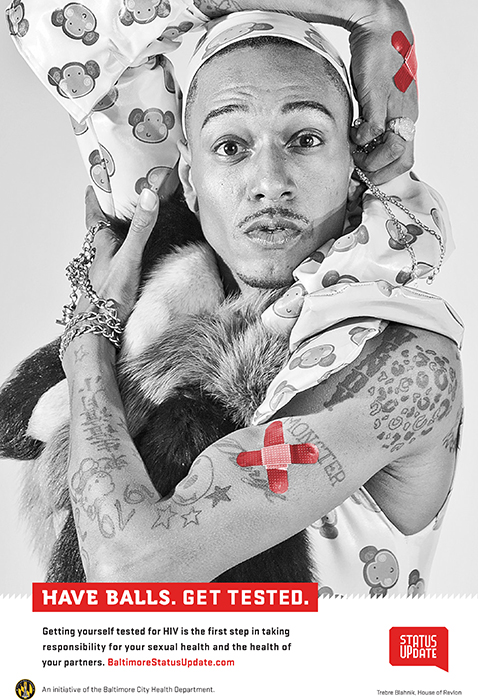

Mike: Initiatives still function as separate entities. What we are seeing is overlap can exist just by sharing the same space. Students walk by each other and see what other people are up to. Everybody becomes a resource for everybody else. When the grad program brings a visiting scholar in, everybody knows about it and is invited. When the CDP invites a researcher studying HIV-AIDS prevention technologies, everybody is exposed to it. Many of the Social Design grad students participate in CDP projects.

What roles do you take on as social design faculty?

Mike: That touches on the social skills that design thinkers need to bring into collaborative environments: knowing when to lead and when to be led. Collaborators have to be nimble in order to play different roles at different times. New students often think that means they have to be the expert, or they have to succumb to whatever the community wants. But in reality, it is the ability to absorb different processes and adapt to different contexts. A collaborator has to be empathetic and humble. People have to be able to play different roles.

Bike Lab

courtesy of mike weikert + ryan clifford

Bike Lab

courtesy of mike weikert + ryan clifford

Ryan: Mike and I are not together in a classroom in the same capacity. Mike is a resource. He comes in at different points during the semester to challenge the students, facilitate the project with a fresh viewpoint, and make sure everyone is on task. Whereas, I am with the students full-time. We find that to be a really effective, educational, team-teaching strategy. With Project M, there is a huge element of trust that the students seek from me. I collaborate with John Bielenberg and we’ve been working together for quite a while. Because we know each other well, when one of us can’t run a workshop, we are able to complete the job without the other person. The same is true of Mike and I. We have an overlap in our philosophy, but we have our own approaches to making that work.

I want students to look at the value of their skill set and see how they can best contribute. We don’t define what meaningful is. We expose them to a ton of different approaches, and they synthesize an approach that works for them on their own. A big aspect to learning about collaborative roles is having students see other designers come together with differing approaches and levels of experience.

Why do you two work well together?

Mike: We both come from the world of graphic design as graduates of Ellen Lupton’s Graphic Design MFA program, although not from the same year. When I was an undergraduate co-chair for the Graphic Design BFA Program and directing the CDP initiative, Ryan was a student in Ellen’s program. Ryan came into the CDP as a student. He was a TA in the CDP and taught in the BFA Graphic Design Program. That’s where we realized that we shared skills and had a good collaborative dynamic.

Ryan: We still work together because we have similar backgrounds. We were both working professionally, doing branding, and we found that it was not as rewarding as it could be. We also have complementary skill sets. Mike is good at seeing the big picture and developing strategies. For example, the majority of the work that we do is based on relationships that Mike has built. He can walk into a room and talk to someone from another discipline for the first time and pitch the CDP, and he does this in a way that makes people want to build a relationship with us. I can do that, but Mike makes it look easy. He created the CDP. He directs the MA in Social Design. What I bring to the table is my teaching ability. I love the classroom experience. I like using all of the things that I learned about design to address social issues with students. I like group dynamics.

How is collaboration integral to social design?

Mike: When we talk about the social of social design, we see it through two lenses. The first, is that everything we do is driven by a social issue or problem. The second part of it, is that we believe that social design is not a solitary graphic designer working on a social issue. It is a collaborative, interdisciplinary, approach. A social designer is not a social designer unless they are social. Collaboration is embedded in the core of social design.

What do you look for when selecting a student?

Ryan: We interview applicants, and then hand-select those who we think will work well together, depending on the project. Students are evaluated by their recommendations and portfolios. We try to match specific skill sets with certain projects.

There is a required baseline design literacy. Students need to understand how to collaborate, which is hard to parse out in interviews. That’s based upon previous experiences, such as past projects or internships, that demonstrate responsibility in a project that is bigger than a classroom project. In the CDP, students have a team of people that depend on them, including their peers and outside partners, so a lot is at stake. We pick a broad range of people with different backgrounds. The group is primarily seniors, with some juniors, post-bacc, and graduate students. We need students who are really mature. The level of complexity that we get is phenomenal.

Mike: We also go to the chairs of each department at MICA to seek out the students who they think are qualified, because we don’t really know. A lot of it has to do with students who have an authentic desire to experience this type of work. It is a learning experience. The CDP is not a fee-for-service studio. At the core, our partners are funding an educational experience.

Ryan: Students have to be flexible, especially with leadership roles. I recognize when students are doing well and give them extra responsibility. I also want students to self-nominate. I want them to assign roles. Letting students have ownership of what they are doing and accepting accountability for that is really important.

What is the collaborative process for a CDP project?

Ryan: The CDP is process-oriented. There is a core design challenge, but we don’t have an agreed-upon outcome for that. The CDP doesn’t have a style because they are responsive to their audience. Our partners and audience are heavily involved in the collaborative process.

Mike: We don’t predefine the parameters of a project. The projects often span multiple semesters. The initial sixteen-week engagement with a partner gets us to having ideas and options. Thus, we have different students who work on a project over the course of three plus semesters. It’s evolutionary.

Ryan: At the end of the semester, students share pitches. The partners usually want to continue the relationship, and we figure out ways to team up again. We are moving into a phase now, where we are doing longer engagements that are written into the semesterly structure from the beginning, so that students know coming in that the first phase for the project is proposals, and the second sixteen weeks is testing and design execution, which leads to the deliverable at the very end.

Does emphasizing the process take away students’ anxiety?

Mike: If there is a deliverable that is due at the end, people go back into their little silos of expertise and comfort and complete the task on their own. When students can free themselves of outcome constraints, that’s when they can really collaborate.

We have partners who are writing us new grants for year-long projects because they have bought into the value of the collaboration and the collaborative process. They no longer see design as just an outcome. That is necessary for good work and good collaboration to happen. Otherwise, the CDP would just be a student-run design shop.

How do you pick projects?

Mike: It has become a scenario of following the money. Who can pay for this experience? But we’ve also realized that there is value to what we can provide these organizations, and that enables them to access more funding. After analyzing the type of work that we have done since 2008, we realized that we have buckets of knowledge in public health, urban space, food access, and the overlaps of those areas. By partnering with institutions that see the value of design in their research, they write us into their grant proposals. Nonprofits are all competing for the same dollar, so when they can write into an application that they are partnering with a design school, and using students to address their issue, that looks good.

Ryan: There is a lesser learning curve when we talk about approaching communications issues, because it’s similar to the way researchers approach public health issues. For both partners, it’s not a prescriptive approach that can be applied to everything. We have to react to the context of each individual issue.

Mike: We don’t only work with institutions from the public sector. For instance, we are working on a project with Whole Foods Market, which is completely in the private-sector. They are giving us marketing dollars. Our partners are all over the board, but I think our cash cow is public health.

Ryan: That said, we are really selective. It’s not just about money, or lineup. We really look to see if there is a relationship between the students and each mission and whether or not it’s a good fit. The CDP is fortunate to be at the point where we can be selective.

What is a CDP collaborative success story?

Mike: When you are able to fondly look back upon an endeavor, challenging moments are suppressed by the impact of good work. There is never a collaborative experience that doesn’t suck at some point along the way.

For me, it was a collaboration between the CDP and a nonprofit called Real Food Farm, which is part of Civic Works, which is an urban agricultural farm in Baltimore City focused on getting fresh local food to residents in food deserts. We really believed the potential of this topic growing legs, because it was vitally important. We persuaded the administration to let us engage in the project before bringing in money. We said, “If you let us do this, we promise you it will bring money in.” So they let us. It ended up being a two year project.

We took students out to the farm. They worked on the farm. They worked with the community to set up farm stands. They not only developed a whole new communications strategy and brand identity for the farm, but they developed a new concept for a mobile market. They bought this old Washington Post truck, and in our studio, we experimented with movable parts and physical boards, which were reiterated multiple times. Today, the Mobile Farmers Market is a huge success. We even got a SAPI grant and grants from the USDA. The Mobile Farmers Market is now a catalyst and icon for that farm. The CDP created value for the organization.

The entire first half of our curriculum for the MA in Social Design Program is about teaming and collaboration. One thing that any collaborative has to have, is a shared objective. A common goal. This doesn’t mean that there has to be a shared vision for what the outcome should be, or the process for which they develop ideas. It doesn’t even mean that everybody has the same ideas. But everyone on the team has to have a shared objective.

With the Real Food Farm project, everybody agreed that people living in food deserts in Baltimore did not have adequate access to fresh local food. Everyone agreed that design could play a role in helping address that issue. You remind people along the way, why they are here. It is not about individual designers trying to make a mark in the community. It’s not the fact that somebody’s logo didn’t get picked, or that somebody disagrees with somebody else’s design solution. It has to do with why everybody is sitting at the table. Embedding that into students is absolutely necessary. You remind students and stakeholders that this is the way collaboration works. Hitting these struggles along the way is just part of the process.

Have you ever had any students who were unable to work within group consensus?

Mike: We’ve definitely had students that have shut down after certain points.

Ryan: Collaboration necessitates effective group dynamics and teaming strategies. A good example of that are the Project M Blitzes, because it is a one week, really intensive collaboration. For the most part, students don’t know each other. It’s interesting in terms of the way the team dynamic works out.

Belfast Muck Lab Project M Blitz, Belfast ME

courtesy of mike weikert + ryan clifford

This is with John Bielenberg?

Ryan: Yes. John is an advisor. It is a travel trip for MICA students. We came up with the Social Design Project M Blitz. We piloted the Blitz in Greensboro, AL. We’ve been to Greensboro multiple times, and we’ve also traveled to Belfast. We do not go to these places to solve a problem. We go to do a project that is inspired by the place.

We get the widest spectrum of students—freshman, sophomores, juniors, seniors, all the way up to MFA students in the Social Design and Graphic Design Programs. We have a range of experiences and skill sets, from people that have been out in the world working professionally for eight years, to students in their second semester of college. Students receive three credits for the week trip plus some extra time spent back at MICA making an outcome.

Discover Greensboro, Project M Blitz, Greensboro AL

courtesy of mike weikert + ryan clifford

The first couple days of the experience starts with an immersion in collaborative dynamics. It is a task-oriented and team-oriented immersion. The point is to build trust, and to reveal what students’ skills and strengths are, so that they can work more effectively together once they get to the big project, which is determined by them. I structure a lot of small, low-risk, action-oriented tasks in order for the students to see themselves better.

Usually by midweek, the students pitch what their big project is. The 2012 class pitched that they wanted to celebrate Greensboro typographically with a mural on Main Street. We like going to Greensboro because it’s a small enough incubator where students can do cool things. Greensboro is really supportive and excited that students want to work here. So the students came up with an idea called Explore Greensboro. It mentions, “learn, build, shop, play, eat, and enjoy.” It’s all inclusive, without cutting anyone out. We pitched it on a Thursday morning at 9 AM, and by 3 PM we had the designs approved. We went to Home Depot and bought $300 worth of paint, and by 6 AM the next morning, it was on the wall.

Discover Greensboro, Project M Blitz, Greensboro AL

courtesy of mike weikert + ryan clifford

How did the group go about deciding to make that?

Ryan: From small prototype projects. Pie Lab is another thing that started with Project M. It has grown into a really great resource space. Pie Lab is a studio in Alabama that we have access to. So we have potluck dinners with them, and sometimes the outcome is an event, instead of a thing. After the trip, we have a small budget, so we can do things like a publication, T-shirts, posters, etc. Because the students receive three credits, the expectation is that once we get back from the trip, we meet a couple more times, and make additional work. But the students determine what they want to do.

What are the Project M Blitz group dynamics like?

Ryan: If there are no difficulties amongst groups, it means there’s probably something wrong, because the students are probably not taking any risks, or not advocating for ideas that they believe in. When students feel strongly about a direction they want to explore, they start to butt heads when things go differently from what they expected. Groups have to have a breakdown before they can come to a breakthrough.

But there are lots of things to help resolve issues. When someone is really combative, I step in. Students are not allowed to tell me why their idea is better. I make everyone go out and prototype. So if we have 12 people, and one person has a differing idea that they want to do, they can prototype it. They can show us why their direction solves a particular problem. We make students put their money where their mouth is with prototypes versus discussion. There is a ton of discussion, but the discussion is tailored towards what are we making as a group and why.

John also talks about process over outcome. If students are only focused on the final outcome, then they aren’t accepting the context for all of the steps that it took for them to get there. My job is to help the students get to each next step and also to address multiple viewpoints. I’ve learned that students need an outlet to release steam. You have to factor in fun group experiences, so that they can build trust. If they don’t trust one another, and they don’t establish a shared ownership and shared outlook, then the collaborative project will not go very well. After the trip, students generally become really good friends and stay in contact, because they have shared this really intensive experience. They can also point to something that they’ve made together.