“I don’t think it is possible to do ‘sustainability’ without ‘generosity.’…The benefit of having a graphic designer at the table is that they are trained in design thinking, and that is helpful because our problems are moving so quickly and designers understand the ephemeral.”—Peter Fine

Peter Fine: Author, Graphic Design: Sustainable Principles and Practices / Laramie WY

uwyo.edu/art/faculty

“i don’t think it is possible to do ‘sustainability’ without ‘generosity.’…the benefit of having a graphic designer at the table is that they are trained in design thinking, and that is helpful because our problems are moving so quickly and designers understand the ephemeral.”—peter fine

How do interdisciplinary and collaborative design elements mesh?

“Cross-disciplinary” has become a mythic buzz word, so people imagine, “Well, if I put together an industrial designer with a graphic designer, and an editor along with some other folks, then things are magically going to start happening.” I just don’t think that’s the case. I think that it has to be interdisciplinary and collaborative, so that means people have an equal voice and an understanding up front, that different actors—from people to institutions to artifacts—can be involved and have agency. I see that the collaborative aspect is vital. Collaboration is the work.

Are you actively teaching collaboration?

Yeah, I would say my teaching practice addresses the skill of students working with other groups and individuals to determine how design is going to be made, and what the outcome is going to be.

How do you teach that?

I started off with a lot of trial and error. Over time, I have gotten pretty good at estimating what people’s different skill sets are and what their disposition might be. You have to get to know the students one-on-one over the course of their education, they have to develop trust in you, and you have to do the same. So it is not a one-way street. It is not a paternal thing. Faculty have to give up a little bit of their authority, if education really is important to them, in order to understand what students are thinking and seeking, and so students can invest in what the faculty are doing.

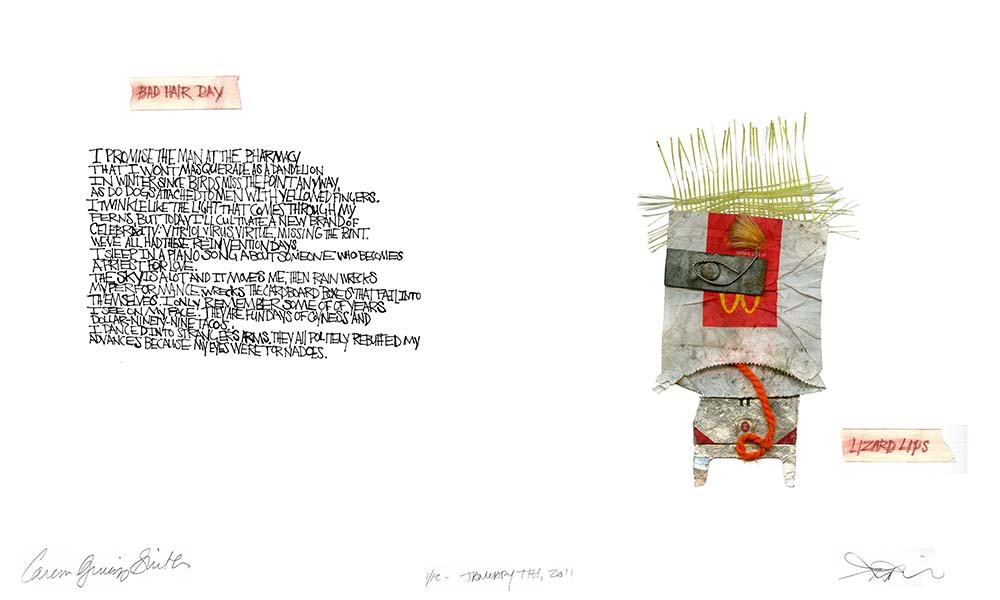

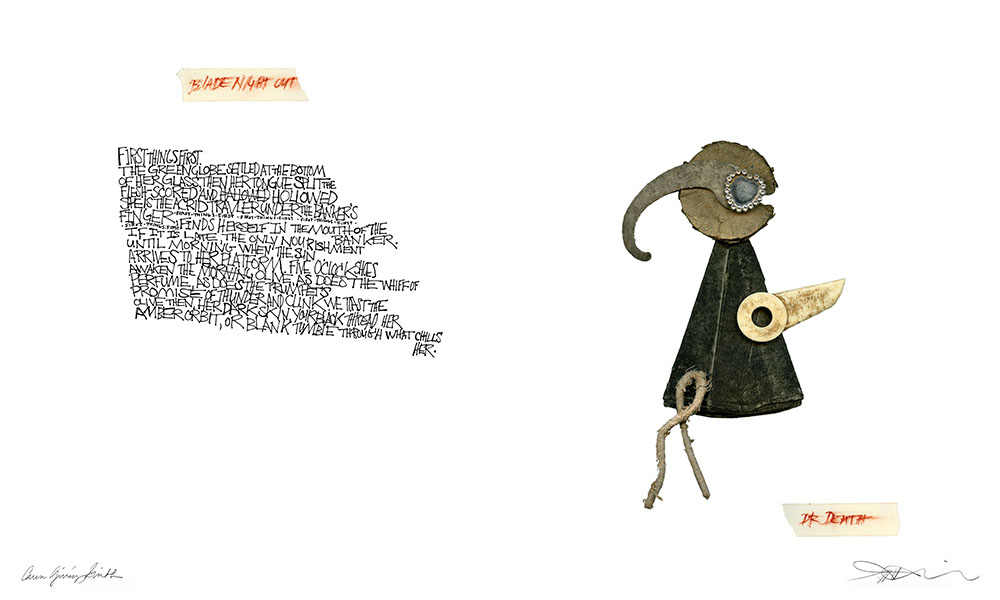

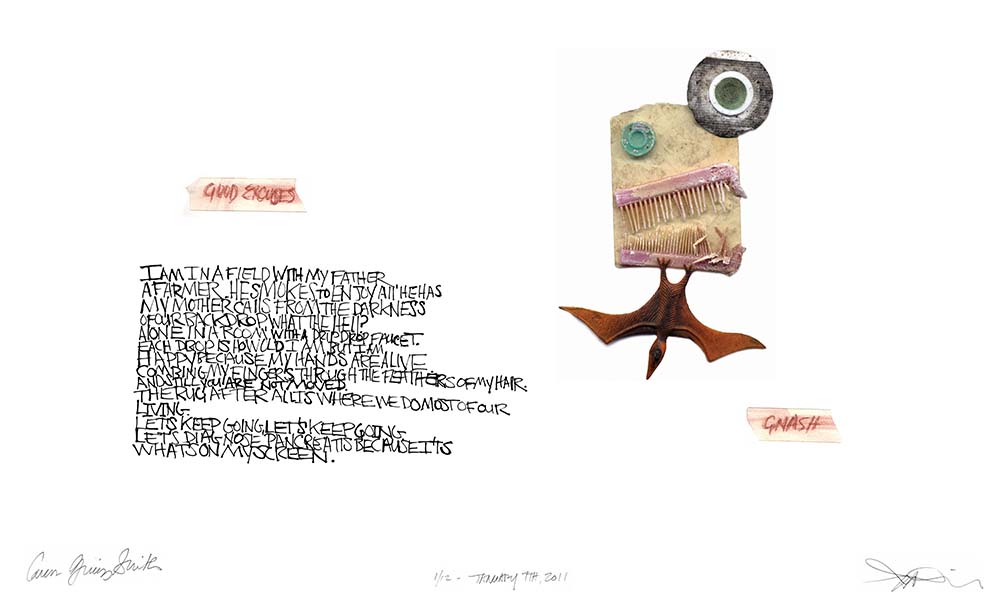

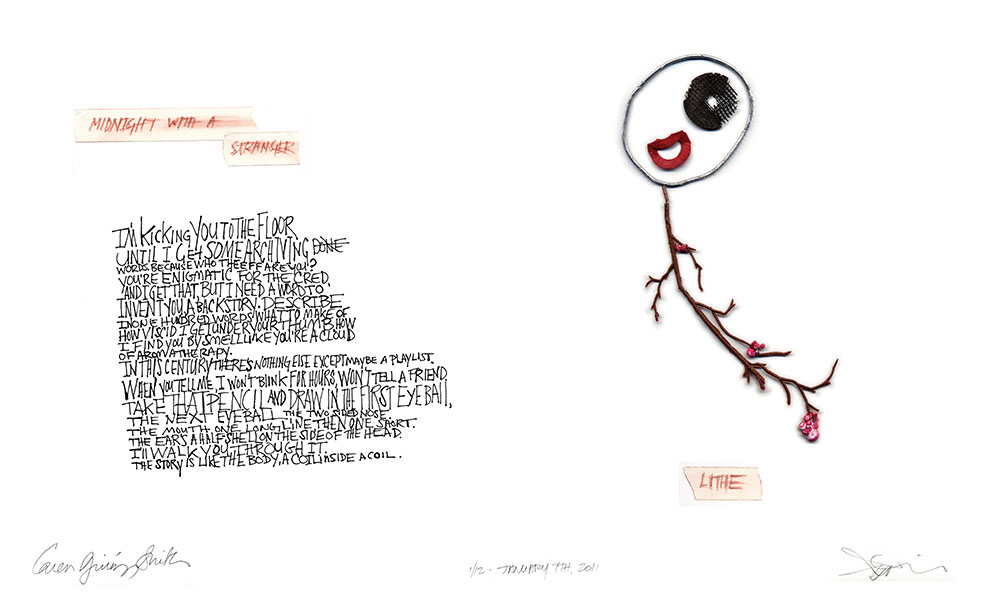

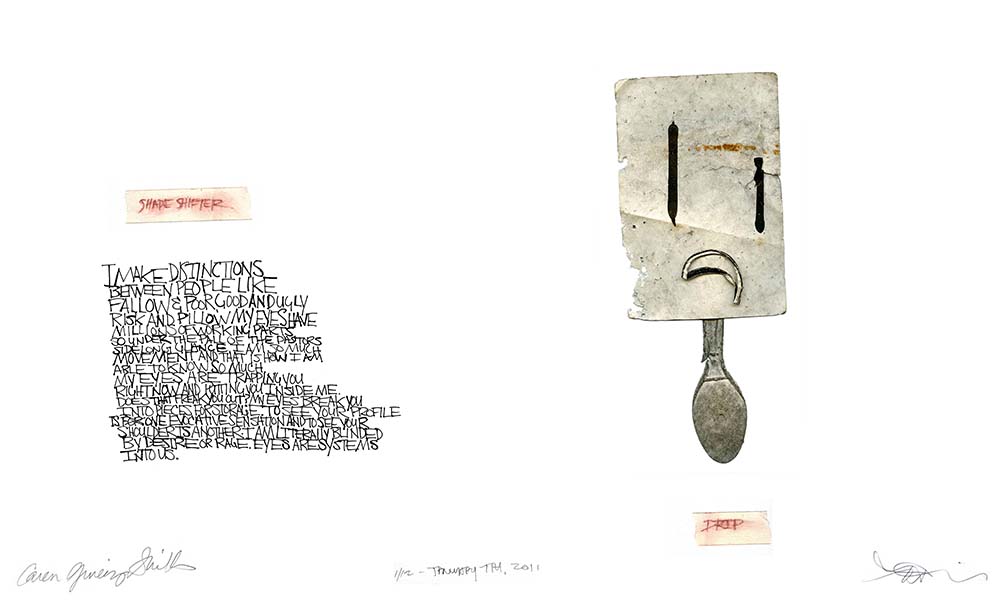

Dis-Assemblage

by: peter fine + carmen giménez smithy

courtesy of peter fine

Sometimes I start off by pairing people. Sometimes at random. Sometimes I let them choose. Then if I find that there are pairs of people that are working well together, I will pair two pairs together and have four. If people self-select, sometimes they do the job of picking who they can work with. That works better than if you pick the group.

When I was growing up, group work was always a pain in the ass. So I am surprised that I decided to get into it. But there are real benefits to it, as long as you’re not doing it to just kill classroom time. It is really important that students learn that they are not the only ones that are going to contribute to the design of something.

Do you emphasize collaboration mostly in a sustainable design context?

Currently, and for a while, I have been researching a sustainable aspect. But I have used the collaborative process in different kinds of classes. For instance, I teach a class on gender and design, and that involved collaboration. When I first wanted to start doing sustainable design, I realized pretty quickly that if it was going to be meaningful, people had to realize that they needed to develop a collaborative skill set along with a graphic design skill set. Sometimes they are the same and sometimes they are different, but they are indispensable if they are actually going to tackle something complex. What we are ultimately talking about is complexity and anxiety. The trust aspect has to do with eliminating the anxiety over dealing with complexity, because the issues surrounding sustainability are really just about complexity. But also, group dynamics are complex and hard to negotiate; mix them together, and people start to see that it’s inevitably going to be about collaboration. Eventually, they get it.

Is there a lot of tension on the student side regarding collaborative work?

There was a lot of tension at the institution I was at prior to the University of Wyoming. The students were really keyed up and defensive about their own individual achievement, outcomes, portfolio, and belief in their original vision. Oddly though, that was happening in a context before I got there, where the students had a very cookie-cutter portfolio. It was a very strange thing. There was a lot of ignorance, and me trying to overcome their ignorance about what creative agency is. They saw their portfolios as being very individual endeavors, but the work was not unique. Every portfolio was coming out the same. I think that tension is latent, and that’s what I’m solving right now.

I am dealing with a different set of students now, so I am not sure if I can answer that yet. It is a different cultural milieu, and there may be a little bit more emphasis on people working in groups, being a little more familial, and less investment in the individual. I think it will take time before they start to decide that they can trust me with what I am doing, and that I am not just leading them astray.

courtesy of peter fine

Other issues are related to that. I didn’t find that the students had a very distinct understanding of the difference between inspirational and original; they were just mimicking work, which is very easy to do in a state context. When I was going to school, creating original imagery was the goal, because there wasn’t that much imagery to even go on. Maybe you could get out a catalog and stock photos for reference, and maybe you could put that on the light table and trace it, and try to get a picture of a lion or a bear or something like that, but really having an original idea and creating an original image was important, and that evolved through the creation process. The other issue is that my students don’t understand appropriation: when to use other people’s work, when not to, and when is that meaningful versus plagiarism?

As long as students are open to things, interdisciplinary collaboration works really well. But you just can’t show up and take another student from another discipline, say an English student, and expect them to join in. It doesn’t work that way. There is a top-down aspect to academia, because of the hierarchy in the divisions. I have never studied it in art school, and I have never taught at one, so I don’t know how the situation would be different there. But in a public university setting, there are definitely divisions—people control different aspects and academic turf is important.

What would be a makeup for designers addressing wicked problems outside of academia?

The issue there: who are designers going to partner with? The biggest problem that I deal with is how I can deemphasize the client-designer dichotomy. The relationship tends to be a top-down thing. The last place I lived in, I eventually started partnering with someone and we came up with an idea for a green design business incubator. It is a matter of finding people who are equally generous in terms of their own personal ethos.

What makes somebody, as a student or professional, a really good collaborator?

Almost all college students that I have worked with, if they are curious, are pretty good collaborators. As long as there is some excitement there for them, and some immediate gratification and long term gratification, and they enjoy the process, and they see a portfolio-ready outcome, then they get excited. What makes someone a good collaborator is simply being open to it. I don’t know where that comes from. It could be part of their personality, their general disposition, or just some socialization. I have found people in the natural sciences, like biologists, are really good to work with. They have a similar interest in close observation. Biologists especially seem to be flexible, and interested, and curious in a way that is similar, but not identical, to how artists or designers work.

What makes collaboration on the topic of sustainability unique?

As far as sustainability goes, I think that addressing it is impossible without collaboration, and without a generous mindset. For instance, a friend of mine called up a person who was involved in one of the first sustainable things going on at MCAD, to ask her advice. She was very new to the subject and interested in sustainability, so she called this person, and this person said, “Well, if I told you how to do it, that would be like McDonald’s revealing their secret sauce.” I think that reflected a couple of really fundamentally flawed ideas. First of all, there is a problem when you compare your sustainability practice to a massive, industrially produced food corporation, and not even understand how that metaphor is entirely wrong.

courtesy of peter fine

I don’t think it is possible to do “sustainability” without “generosity.” I think the problems are just so “wicked” that you have to collaborate with people. The benefit of having a graphic designer at the table is that they are trained in design thinking, and that is helpful because our problems are moving so quickly and designers understand the ephemeral. Designers can produce multiples very quickly. They are very iterative. That visual thinking, connected with materiality, is really powerful. Even if my students don’t become graphic designers, which is fine, by studying sustainability through the lens of design, they would be head and shoulders above everyone else in terms of creative problem-solving. It seems obvious, but it doesn’t happen very much.

Why doesn’t it happen?

I think it is because of the way education is set up, and the scale. Education happens on a scale that is too large; it is not really human-centered.

How does design education need to evolve to better address social issues?

I think design should be a part of the liberal arts: there should be a component to the liberal arts requirement called “design,” and everybody should take a design class, because it bridges between humanities and sciences. I wrote in my book that, it’s a little bit polemical at this point, but I think the scale of things needs to change. The classroom sizes need to be smaller. Expectations need to be smaller. And skills need to build on each other—whether it’s about graphic design, industrial design, systems thinking, scale, or tools. We need to stop thinking about problems in terms of inventing something totally new in order to eventually hack something new.

How did you get interested in collaboration and sustainability in the first place?

I was teaching history of graphic design, which over time, I have broadened to include the social history of design and how that affected all of these different aspects of culture. When I was using the Philip Meggs book, I asked them to read up to the 18th century on their own. I would just teach the industrial revolution and forward. In doing that, I got really interested in consumer capitalism and industrial capitalism, so I ended up teaching a lot of stuff related to that, and I started having students focus on those issues. Their impression was that I was being critical of consumption and I thought I was just talking about design.

I went to this conference, a design educators conference in Philly, and was on the same panel as someone who was talking about sustainable design. That was the first time I was inspired. I told that person they should write a book about this, because at that time, nothing existed. There wasn’t anything for graphic designers. Then we started working together, but that collaboration failed because another party was involved and their role wasn’t defined. It wasn’t a sustainable relationship.

courtesy of peter fine

On that note, what makes a collaboration effective?

It has to be a partnership. It can’t be that one person has a vision, and another person is supposed to realize this vision, and the designer has to be an author and/or entrepreneur. They have to be equal partners. That doesn’t really exist in any of the structures of where design education or practice is at now. The only example would be those innovation design firms like IDEO, where they come to the table and see themselves that way, so they are treated that way.

Does that mean design has to represent itself differently?

I believe so. Art and design have different identities in different cultures and societies. In the US, it has been design as a business or design as a management system. In France or Italy, it is still considered art. In Germany, it is very technical, and very much about the rational. It depends on the culture.

I go to conferences, and I hear a lot of people talk about that. Maybe not explicitly, but it is definitely there all of the time. The first design conference that I went to, I met the guy who had done all of the MTV’s early stuff. He was the funnest guy there. I think for a while, graphic designers were sort of envious of people who were doing things that were more creative and intuitive. Maybe something got lost for several years and had to come back.

Can you detail the work you do with Carmen?

The collaboration that I do with Carmen Gimenez Smith is really interesting. There is a lot of breadth to the work and it goes in different directions. It feeds me in certain ways. It has helped me to develop some areas that I had not developed before. For instance, it has allowed me to get published in a literary context, so there is a lot of personal fulfillment out of it, and the collaboration does make my work better.

Originally, I was really reticent to work together, because I was thinking of those collages as having some sort of life of their own, and I imagined that it would be a book. I imagined that I might write something in response. She came up with the idea of me hand-lettering the work. And I suggested we both do it. So eventually we just sat down and both tried it. But we didn’t really like anything that was happening. Over time she started producing more writing—she wrote a bunch of short things. She writes a voice for the persona of these characters, like little portraits. She would try to find their voice. But she would also do a collaging type of process with the text, where she would bring together old bits and pieces from other notebooks and things that she had written and scrapped.

Eventually, I just relaxed and I was able to take those texts and re-inscribe them. I eventually came up with a form of hand-lettering that I liked. I really don’t like my handwriting. I have never done hand-lettered work. I had always been more of a typographer. But I tried it. When I stopped worrying, and let go of that sort of graphic designers’ control, the result was serendipitous. It was highly intuitive and experimental. She worked in parallel to me, and then I responded to her. Then we put the two parts together. It was a very enjoyable process. I think that is why it makes our collaborative work. It took some time to figure our process out. It took repetition and having free time.

It is very disconnected, in some ways, from my other stuff, but in other ways, it’s not. Now I see parallels between that and the sustainability stuff—especially with materiality, the analog/digital, and the verbal/visual.

Are you working physically in the same space?

No. We are doing that remotely now. Even though we lived in the same town, I would send her the images, she would write to those, and then send it back to me. But we do layout together.

Are all of these collages pre-existing?

I generate new ones all of the time. Right now, I probably have six or seven in my studio that need to be scanned and sent to her. I scan them, which is an important part of the process. First, I will quickly photograph them and send it to her so she can take a look and see what she thinks. We both respond pretty quickly when in production-mode.

Do you ever edit the writing when you get something back?

No. I don’t edit, but I make a lot of mistakes. I enjoy the mistakes and I let the mistakes stand. And she lets them stand too, which is very surprising. There has only been one time where she didn’t think that it was working.

What’s the timeline for all that?

It varies. It can be really quick, like it can happen in a couple of days. Sometimes it takes weeks. Carmen tends to work in spurts, since she has several projects going on.

courtesy of peter fine

If you had a dream project that you could run, or work with anyone you wanted, or have a piece of gear, what would your dream gig be?

I don’t know, because right now I am struggling with direction. For instance, I am inspired with the work that I am doing with Carmen. We are talking to a couple of different presses, and it will be published as a poetry book. That is kind of cool for me. It puts me in a different genre altogether.

How important is it to cross discipline-boundaries?

I think it is vital if you ever want to do anything interesting. But it is more than just being interdisciplinary. People have to be interdisciplinary in their thinking, and they have to collaborate in their working. You can’t mistake the cross disciplinary model for interdisciplinarity, where often times a business person is paired with an engineer person and together they hope to come up with a good product idea. Both of those people have to be interdisciplinary within their thinking and their working in order for that relationship to work. They have to break down whatever internal impediments might exist within themselves in order to do something truly creative. If you look back at what happened with Apple, Adobe, and Xerox, there were a lot of people pushing and pulling simultaneously. Some people got more of the credit than others, but it truly was a very big mix of people at the start of the digital revolution. Interestingly enough, it all started at a small scale. People were taking really complex systems and trying to move them to the desktop. It took a different way of thinking, but they were all thinking differently and getting together.

What do designers have to do to enable people to work in that vein?

Rethink the entire educational system. An example of what needs to change, and what doesn’t work, is combining a business model with an educational model. This is what we are currently doing in our culture, and have been doing for 25 years. It is not working. The debates over charter schools, teaching to tests, and curriculums need to be resolved.

If America is saying that education is a commodity, it’s not going to work. Until people get past that idea, I don’t know what designers can do. There is a mistake in trusting the business model and technology. It’s a miracle that we are still able to teach. So that implies that teaching is an important thing, but it’s not something that people are really interested in fixing right now.